The Talua Theological Training Institute is situated on the remote island of Santo, part of the archipelago nation of Vanuatu in the South Pacific. Formed in 1986 by the Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu out of two antecedent institutions, it has a very limited supply of solar electricity, supplemented for 90 minutes every evening by a diesel generator. There is no television signal. Short-wave radio occasionally picks up broadcasts from an Australian station, but it can’t receive the FM channel in Luganville, the regional capital 25km away. The postal service is unreliable, with outgoing foreign mail regularly lost. Transport from Luganville is usually in the back of trucks carrying copra sacks. The internet service, which is feeble at best, has been cut off since late January.

This is hardly the ideal location for a higher education institution. But Presbyterianism is Vanuatu’s largest denomination, and it needs its pastors. The church-administered college offers certificates, diplomas and bachelor’s degrees in religious and ministry studies to members of Protestant churches. Substantial support comes from Presbyterian churches in Australia and New Zealand, which supply some lecturers, and the college is also assisted by unpaid foreign Christian volunteers, who teach and work on construction projects. A conservative Christian Australian high school teacher in New South Wales also controls the website, Wikipedia entries and the firewall. He blocks Facebook and YouTube, and he once denied access to a text of Romeo and Juliet because of “sexual content”.

Vanuatu is not only in need of pastors, however. School teachers are also in desperately short supply. In 2012, the indigenous ni-Vanuatu staff at Talua – who have master’s degrees from institutions in the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and Fiji – joined forces with students to propose a broadening of the curriculum. This was partly out of a desire to compete with the local branch of the University of the South Pacific, which trains pastors in practical skills. But they also wanted to increase the proportion of tertiary-level students in Vanuatu, which rates 180th out of 181 in the world on that measure (although it has significant numbers of people training in other countries, including China, Cuba, France, Fiji, Papua New Guinea and the US).

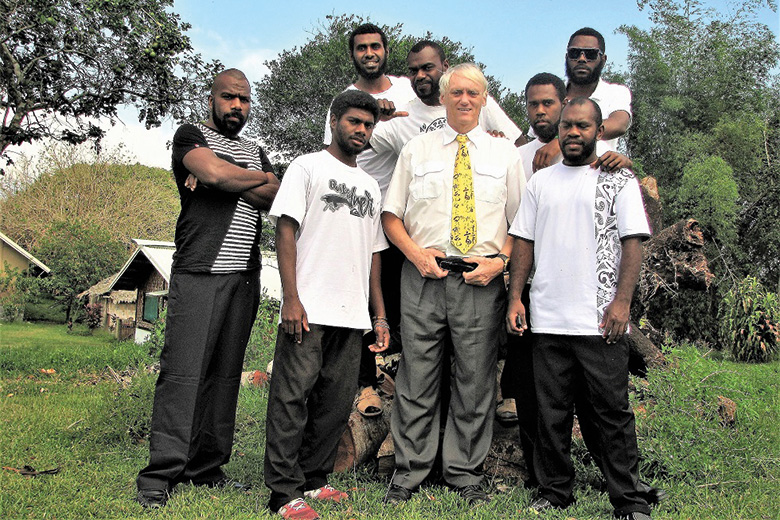

Last August, the Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu’s annual conference agreed to work towards the establishment of a university. Talua’s director, Selerick Michel Kalpram, responded by encouraging the introduction of other residential and distance courses, and appointed me as administrator and English teacher.

My journey to Talua was long in more ways than one. I am in origin indigenous Siberian Evenki (traditionally, reindeer herders and fur trappers) and Chukchi (often referred to as “Russian Eskimos”), but I was raised in what was then Tanganyika, where my father settled after serving there in the First World War.

I graduated in African history from what was then the School of Oriental and African Studies (now Soas, University of London) in 1968 and immediately hitch-hiked back to my African homeland, by then known as Tanzania, via Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt and the Nile. For two years, I taught at a new Catholic mission secondary school for girls at Kibosho on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, alongside mostly gap-year British and Irish school-leavers waiting to start their studies at Soas or Oxbridge.

We had pitiful resources, were paid a fifth of the regular local wage and relied on typewriters and Gestetner duplicators to produce teaching material for Cambridge Overseas GCE O‑level exams. However, both the teachers and the girls were so highly motivated that we succeeded in laying the foundation for what became, and has remained, one of the two top private (with minimal fees) girls’ schools in Tanzania.

I was also chairman and editor of the Kilimanjaro region’s historical association. I published studies on the local Masai and Chaga dialects and wrote a history of West Africa in Swahili for high schools. I was astonished at local people’s depth of knowledge on language, history and other issues. This encouraged me to campaign for the provision of low-cost, high-quality rural education and local academic research in these areas.

My own background made me instantly sympathetic to the cause. The initial phase of Russian colonisation of north-east Siberia, in the 18th century, decimated 80 per cent of our people. Most Siberian aboriginal children are now sent away to boarding schools. Education is in Russian, which helps wider communication because Evenki dialects are not mutually intelligible, but children quickly learn to hide their identity as if it were a source of shame. The Chukchi lost a court case in 2014 against the publisher of a Russian dictionary that described them as “naive and narrow-minded people”, and Evenki have a short life expectancy because their suicide rate is high. Evenki educational activists in Yakutsk, with whom I am in touch, are desperate to build better local educational provision that can make their people proud of their heritage.

So I knew how it felt to have your culture, religion, language and economic system deemed worthless and in need of immediate replacement. I understood how devastating

the psychological effects could be.

From 1970 onwards, I became heavily involved in the Tanzanian-based military and political struggle against apartheid South Africa, and the campaign to restore democratic rule in the Kingdom of Lesotho. Consequently, and certainly inspired by the Kibosho experience, I worked with two political parties on schemes designed to provide low-cost, high-quality tertiary education in a future post-apartheid South Africa and a democratic Lesotho.

The parties took their ideological inspiration from Anton Muziwakhe Lembede, the early 20th-century Zulu intellectual who, despite his own poverty, believed that oppressed peoples were capable of achieving anything. Unfortunately, the University of London had withdrawn its external programme whereby students could study cheaply alone or through correspondence colleges. So, in 1977, I implemented a promising scheme in Kenya: a modest degree programme called Lincoln University in Kenya. By 1979, it had been closed when the supportive minister of education was replaced by a powerful rival, whose promised external programme never arrived.

In 1981, I persuaded a sympathetic Arab government to grant $1.8 million (£1.4 million) to establish a “University of Azania” in Zimbabwe, for exiled southern Africans. However, this was shelved after it incited political infighting within the ZANU‑PF government, with two ministers almost coming to blows over it.

From 1970 to 1986, I was the only non-African member of two allied Tanzanian-based guerrilla armies. This experience culminated in a 225,000-word PhD thesis, examined by the University of Bremen, on political parties set up by peasants, migrant workers and township activists in Lesotho and South Africa that had been forced into guerrilla warfare after being banned or having had their election victories ignored by the incumbent powers. Particularly inspiring was the fiercely independent Basutoland Congress Party, whose members once built a road parallel to a government–sponsored one to show that -Lesotho didn’t need foreign aid.

Democracy was restored in Lesotho in 1993, and I was officially thanked for my assistance during the years of dictatorship and military rule. However, political chaos quickly resumed, and my detailed, highly critical doctoral account of the liberation struggle (still frequently downloaded from Academia.edu and Scribd) ensured that I had no place in the “new” South Africa, which ended apartheid the following year.

Having quit politics, I migrated to Australia and served as an unpaid volunteer language trainer for the Australian army’s UN Rwanda Force, and then for its mine clearance operations in Mozambique.

But my focus was mostly on the provision of low-cost, high-quality education for refugees and low-income countries. Since 1996, I have taught and researched at 17 universities in all six continents, including a period as visiting fellow in Afghan women’s education at the University of Oxford.

Unfortunately, I have been swimming against the tide. I did not have to pay for my German doctorate. Now, however, university education in English–speaking countries has not only become big business, with high tuition fees for overseas students, but it has also been geared to lucrative careers, very often with international agencies based in first-world cities. In addition, textbooks – including digital versions – have soared in cost, and educational short-wave radio and television seem to be extinct. Students in poorer countries are hard-pressed to afford a laptop and access to the internet, never mind tuition fees.

Meanwhile, around the world, tertiary education is often linked to ostentation. In Tanzania, a university cannot be founded unless its campus is a certain size. In China, university architecture is monumental. Low-cost and, especially, distance tertiary education are usually despised.

But I persevered, working with a number of groups and institutions to establish quality residential and distance tertiary education at minimal cost. Beneficiaries include various groups in Ethiopia (where I have a home), especially the Beta Israel Jewish community. They also include exiled Burmese groups, exiled Afghans and poor populations in Guyana, Jamaica, East Timor, Gabon and Laos. But most promising of all is Talua.

Although I am not a member of the Presbyterian or, indeed, any church, I had volunteered at the institution on two previous occasions, for three- and eight-week periods, before my appointment as administrator of the expanded degree programme. Vanuatu is an attractive location. Known as the New Hebrides before its independence from joint British and French rule in 1980, it is frequently ranked the world’s happiest country. It is a major attraction for researchers on successful non-industrial societies, having also been rated the most ecologically efficient country in achieving high well‑being.

Most of the population of 250,000 live in isolated, self-sufficient rural communities dependent on agriculture and fishing. There are 113 local languages, with English, French and Bislama as national languages. Bislama, the lingua franca, is an English-based creole that English speakers pick up very quickly. In a way, it is a sociolinguistic protest that says to the former colonial powers: “You didn’t accept us as equals, so we are not going to have your languages as our national uniting tongue.”

Talua’s envisaged wider curriculum includes primary industry development, education, medical care, accountancy, business management and land issues. But, despite the efforts of individual missionaries and the establishment of many educational centres in Vanuatu, there has been a historically powerful reluctance by missionary organisations to allow ni-Vanuatu a greater role in their own affairs. The first indigenous pastor was ordained a full 60 years after the arrival of the first mission-aries.

Unwilling to move beyond evangelisation at Talua, long-serving Australian and New Zealander missionaries have opposed the institute’s introduction of non-religious courses, let alone the establishment of a university. And when the Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu chose me as Talua’s English teacher, in preference to missionary-backed candidates, the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand – the main Presbyterian church in New Zealand – spitefully withdrew its funding for the advertised salary (£12,618 a year, plus medical insurance) knowing that I had already agreed to work for free as the administrator.

Hence, when I arrived in Vanuatu, I found that I had no contract and was expected to do two jobs at my own expense. Fortunately, the Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu, which feels very bad about the situation, is extremely supportive, and Talua staff and student families frequently drop off vegetables and fish at my house.

At first, a free general degree was planned to begin in March 2017, starting with English, history, accounting and management modules. This was because Talua possesses a great amount of relevant video, audio and PDF book material that can be placed on 32GB memory sticks for use with small, solar-charged laptops. However, there is no accommodation available at present for extra bachelor’s students, and possible solutions are still under discussion.

Meanwhile, the doctoral programme is already under way. After lengthy discussions with the church and the education department, the five Talua lecturers with master’s degrees have enrolled free of charge for in-service training on how to write a PhD thesis. Their topics are land issues, language, religion and history. The idea is that once they have their doctorates, the government accreditation authority, the Vanuatu Qualifications Authority, will be able to draw on their local expertise to assess standards at doctorate level.

At present, besides myself, academics at residential universities in Austria, Belgium, the UK, the Republic of Ireland, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the US have volunteered to guide students free of charge, and to pay for Jstor digital library services. This will be the first time that doctoral studies have been available in Vanuatu, and it is a huge step forward for higher education here. Talua has also given the go-ahead for the expansion of bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees by research and coursework. Hopefully, philanthropic academics will be willing to assist with these, too.

Life at Talua is isolated but very pleasant. The institution has its own untouched island, a large neighbouring farm, sports fields and a good library. Students and staff regularly dive for lobsters and fish. Vanuatu is free of the poisonous snakes, crocodiles and murderous “raskol” gangs that plague Papua New Guinea. It has jailed corrupt government minsters and got rid of Russian money launderers.

I intend to spend half of my time in Vanuatu and the rest working as a research assistant for the five ni-Vanuatu PhD candidates, scouring archives, libraries and databases in Australia and elsewhere for the information they need. I will also be looking for assistance for the Talua scheme from universities and other organisations in Europe, Japan and South Korea.

In addition, I remain involved with the Beta Israel of Ethiopia, who regard me as the most sympathetic foreign academic concerning their traditions and beliefs. In 2015, the Israeli ambassador to Ethiopia, herself a Beta Israel, asked me to assist in establishing a tertiary institution for them. The Talua project will provide useful lessons for realising that plan. And the children of former colleagues in the South African conflict, now campaigning for free or cheaper university education, also keep in touch.

I don’t envisage my global adventures coming to an end any time soon.

[“source-timeshighereducation”]