/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/57320961/453615377.0.jpg)

“Schools are segregated because white people want them that way. … We won’t fix this problem until we really wrestle with that fact.”

That’s what Nikole Hannah-Jones, New York Times Magazine writer and recipient of a prestigious “genius grant,” told me in a recent interview. “Genius grant” is the popular term for the MacArthur fellowship, a no-strings-attached $625,000 grant awarded to 24 “exceptionally creative people” each year.

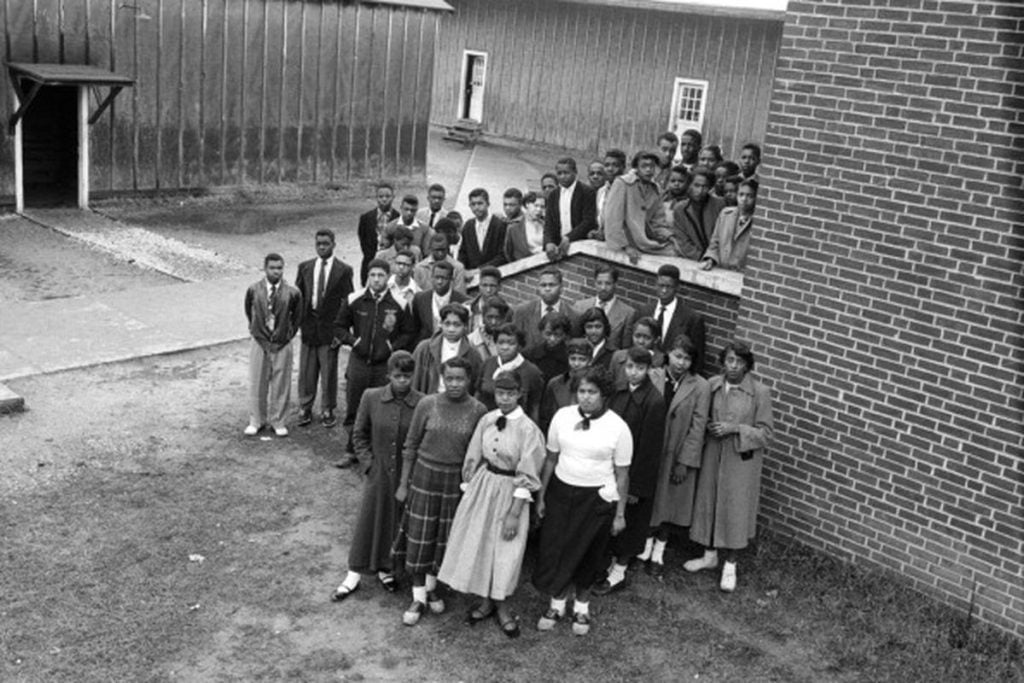

Hannah-Jones was selected this year for her probing work on segregation in American society, particularly in housing and education. She’s probably best known for her two award-winning stories “Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City” and “The Problem We All Live With.”

I reached out to her this week after her grant was announced. We talked about the myths surrounding segregation in America, why it’s so damn hard to explain structural racism, and why she remains deeply cynical about America’s future.

“This is the story of the black experience,” Hannah-Jones told me. “People want hope. They want to believe things are getting better for black folks. What I’m arguing … is that things will never be right. An improvement doesn’t make things right; it just makes them a little better.”

Our full conversation, lightly edited for clarity follows.

Sean Illing

First, congrats on the MacArthur genius grant. Did you have any idea that was coming?

Nikole Hannah-Jones

None. The call came out of nowhere. I was as surprised as anyone.

Sean Illing

I have to ask you how you think about the role of investigative reporting in our society, and why you think it’s so important that we have more people of color working in this world.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

Because investigate reporters are the vanguard in so many ways. These are the reporters who reveal how the powerful are harming the weak, who speak to the most vulnerable in our society. We know that investigative reporting is very critical, but it’s also among the whitest parts of our field. And that matters because there are stories that we just don’t tell or see or believe when all of the investigative reporters are white.

Every journalist is seeing stories through the lens of their own experiences and their own backgrounds, so we need diverse investigative newsrooms in order to tell all of the stories that need to be told.

Sean Illing

So I think of you as a kind of myth buster. On issues of race and institutional bigotry and segregation, you try to show how the inequalities we see are deliberately built into the system; it’s part of the design. How do you think about this in terms of your approach to your work?

Nikole Hannah-Jones

When I give talks, I often put up a slide that shows these disparities in health care, education, employment, etc., and I say, “Is anyone surprised that black people fare worse in all of these things?” And no one’s surprised. We just accept this. It’s just the way things are. So then we don’t have to do anything about it.

Whenever I’m looking to write a story, I don’t think it’s enough to just say that racial inequalities exist. We have to write stories that show why, that show that someone is responsible. So I approach stories by figuring out if I can show how the past got us here, and how current policies are compounding this problem.

We have to challenge how we got here and make sure people understand that there are people, right now, who can be held accountable for it.

Sean Illing

What do you think people least understand about school segregation in America?

Nikole Hannah-Jones

What’s important to understand is that segregation is not about test scores; it’s about denying full citizenship to a caste of children who have not, for one day in this country, been given full and equal access to the same educational resources as white children. So it’s not really about closing the test score gap. Segregation is about separating black children from white children, and therefore separating black children from the same resources as white children. I think we have to talk about it in these terms.

What people also don’t want to acknowledge is that schools are segregated because white people want them that way. It’s not simply a matter of zip codes or housing segregation or class; it’s because most white Americans do not wish to enroll their children in schools with large numbers of black kids. And it doesn’t matter if they live in the North or the South, or if they’re liberal or conservative.

We won’t fix this problem until we really wrestle with that fact.

Sean Illing

Why is segregation, in housing and education, the primary barrier to equality?

Nikole Hannah-Jones

Segregation in housing is the way you can accomplish segregation in every aspect of life. Housing segregation means that certain jobs are located in certain communities, that certain grocery stores are located in certain communities; it determines where parks are located, if streets are repaired, if toxic dump sites are built nearby. Segregation accomplishes so many other inequalities because you effectively contain a population to a geographic area and suddenly all the other civil rights law don’t matter.

We don’t have to discriminate if we’re living in totally segregated neighborhoods; all the work is already done. If you look at the history of civil rights legislation, it’s the Fair Housing laws that get passed last — and barely so. Dr. King had to get assassinated in order for it to get passed, and that was because it was considered the Northern civil rights bill. It was civil rights made personal; it was determining who would live next door to you and therefore who would be able to share the resources that you received. The same is true of school desegregation.

Education and housing are the two most intimate areas of American life, and they’re the areas where we’ve made the least progress. And we believe that schools are the primary driver of opportunity, and white children have benefited from an unequal system. And why is this so? Why have white people allowed this? Because it benefited them to have it that way.

Sean Illing

It’s easy to point to neo-Nazis in the street or to white supremacist websites as examples of racism. But the real racism, the racism that ruins lives and cuts down generations, is the quiet racism built into housing and zoning policies, into segregated schools, into obscure laws and social policies. That’s the stuff that’s hard to concretize — but it’s kind of everything.

How do you try to flesh out these links in your work?

Nikole Hannah-Jones

It’s really challenging because it’s complex and multilayered. So much of this is embedded in a history that stretches back centuries. People can only see things as individuals. They say, “I’ve worked hard for this and now you’re saying I don’t deserve it. You should just work hard too.” That’s an easy argument that everyone understands. Structural inequality is much harder to understand, and you can’t say it in a sound bite or a few sentences. And I think there’s a fundamental desire on the part of some white people to not want to deal with this history.

So how do you fight that? Even if you’re writing a very short piece, you have to always be adding that context — how did we get here? What was the policy or history that led us here? Probably two-thirds of my work takes place in the past and a third takes place in the present, because I understand that I can’t get anyone to care or understand if I don’t explain this history and connect it to the present in clear ways.

So I see my work as trying to excavate the history, the practices, and the decisions that have led to this disparity.

Sean Illing

I’ve always believed that human beings are conditioned creatures, and that most of our social outcomes are engineered. But I interviewed Glenn Loury last year about this, and while he didn’t change my mind, I think he makes an argument worth engaging with. He doesn’t deny that there are historical and structural factors that impact the lives of African Americans today, but he pushes back against attributing too much to those factors because it robs people of their agency.

I’m curious how you respond to this line of thinking.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

Of course people have agency, but everyone doesn’t have equal agency within a system of constrained choices. And I’ll give you a clear example: Harriet Tubman exercised her agency when she ran away, when she stole herself free. So are we then saying that every enslaved person could have been free because Harriet Tubman got herself free? I don’t think anyone would argue that. People would say that the institutions of slavery, all of the laws and policies that had to be changed or transgressed to get free, virtually made it impossible for most black people. Just because you have the ability to do something in theory doesn’t mean that you actually can.

Unless Loury’s willing to argue that the only reason all of these people were enslaved is that they choose not to be free because they didn’t exercise their agency, then I think his argument doesn’t hold water.

Sean Illing

I guess this is where I struggle a bit, especially when reading someone like Ta-Nehisi Coates. There’s a sense of fatalism lurking beneath it all, like these injustices are so deeply embedded in our system that we can’t ever hope to correct them. I understand it intellectually; I just don’t know where to go from there.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

The experience of black people in this country is not a happy story. It’s a story of resistance, of black people always pushing to have their full humanity granted. But it’s been a history of struggle from the very beginning.

I took my 7-year-old daughter to the African-American Museum of History and Culture in DC recently, and you spend most of your time on the first two floors — the first covering slavery and the second covering Jim Crow. And my daughter kept asking me, “Why?” She didn’t understand why white people would do this. I realize as I’m explaining to my child that it’s really impossible to explain the logic. We just accept that this is our heritage because it is our heritage, but it’s impossible to make sense of it all.

This is the story of the black experience. People want hope. They want to believe things are getting better for black folks. What I’m arguing, and I think what Ta-Nehisi is arguing, is that things will never be right. An improvement doesn’t make things right; it just makes them a little better.

Black people are still fighting for equal citizenship rights. Millions of black children are still in schools that look just as if Brown v. Board of Education never happened. Generations of black people are still trapped in urban ghettoes. The black unemployment rate, in the best of times, is still double that of white Americans. Black people face discrimination in every sector of American life.

So when people want hope, I wonder: Hope for what? To me, until black Americans are treated as full citizens, it’s immoral to expect people to be satisfied just because there’s forward progress. People want hope and absolution instead of working to destroy a system that still holds black people last in almost everything.

Sean Illing

I don’t really believe in absolution and I’m just about out of hope, but I wonder if there’s at least the possibility of a future that isn’t hopelessly marred by these sins, for lack of a better word.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

No, there isn’t. But that doesn’t absolve us of the responsibility to try to make things better.

Source:-Vox